V ♦ I ♦ E ♦ W ♦ S

(The Official EDGE Blog)

OCTOBER 2019

By Yannis C. Yortsos, Brandi P. Jones, Gisele Ragusa, and Timothy M. Pinkston

By Yannis C. Yortsos, Brandi P. Jones, Gisele Ragusa, and Timothy M. Pinkston

USC Viterbi School of Engineering, University of Southern California

presented June 26, 2017 ASEE Annual Conference, Columbus, Ohio

Engineering an Educational Transformation Based on Analogies with Chemical Reaction and Flow Processes

This white paper presents a new approach, based on parallels with chemical kinetics, that addresses in part the well-known, long-term challenges of attracting, supporting, retaining, and graduating traditionally underrepresented students in engineering colleges and programs. A model based on chemical reactions and flow processes is proposed as a possible means to achieve efficiencies premised on reaching a parity objective and which underscores the need for ownership of the processes by engineering institutions. Institutional ownership of the processes and their accountability for the outcomes will likely lead to diversifying engineering workforces at levels yet to be reached nationally. The model assists in the decomposition of challenges facing higher education (and particularly engineering education) into elemental steps and calls for adapting control strategies as best practices. It underscores the challenges associated with the points of transition from the upstream to the downstream parts of the flow process, where the ownership of the input may be widely distributed, and calls for participation of entities other than the individual engineering institutions who own the various contributions of the process. The model also brings to the fore issues that cannot be accurately captured with simple quantification, such as inclusion, and how those issues may be viewed in the present framework. It further suggests the possibility of alternative ways and platforms that will enrich and enhance traditional university-based educational approaches.

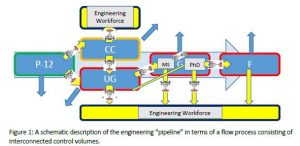

The Pipeline Model: A Useful Analogy with Flow and Reaction Processes

The persistent lack of diversity in engineering and technology is well known. The reasons for such persistence are varied and numerous and have been amply described in the literature. But increasing the diversity in the engineering workforce is a profoundly identified need [1], [2]. As in many related such challenges, robust, impactful and lasting changes must recognize the pipeline character of the problem, and the characteristic times and time horizons involved.

The following schematic provides a model of a traditional engineering education in terms of a generic “flow diagram”

This is an excerpt. For the full document, click here.

SEPTEMBER 2019

By Gretal Leibnitz, Ph.D. published August 13, 2019

Gender Diversity / Gender Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion Strategies

Competitive Advantage through Gender Equity & Considerations for Effecting Change

Deans work hard to create competitive advantage for their colleges. Shaping a college that is diverse, equitable, and inclusive is a powerful way of forging excellence AND competitive advantage. As former president of the National Academy of Engineering, William A. Wulf, succinctly put it “…sans diversity, we limit the set of life experiences that are applied, and as a result, we pay an opportunity cost – a cost in products not built, in designs not considered, in constraints not understood, in processes not invented.”[1]

The business case for the competitive advantage of gender diversity is well established and compelling. Internationally recognized economist, Scott Page, provides clear evidence that leveraging diversity can improve organizational performance [2]. Further, the 2018 McKinsey & Company report, details the evidence-based business case for diversity, concluding: 1) the relationship between diversity and business performance persists, 2) companies with gender diversity on executive teams outperformed, homogenous executive teams, 3) that gender is just one way of capturing competitive advantage (e.g., ethnicity/cultural diversity, LGBTQ+, age/generation, global experience), and, 4) there is an “Opt-Out” penalty when there is little gender, or other, diversity [3, p.1]. Finally, internationally recognized gender researcher, Virginia Valian, provides research evidence for the importance of gender diversity, equity, and inclusion in her 2018 book with co-author Abby Stewart, An Inclusive Academy: Achieving Diversity and Excellence” [4], as well as key talking points specific to the benefits of ensuring gender equity within an academic setting [5].

Consequently, the issue is not so much IF gender diversity matters, but HOW to drive organizational intent, to action. The commitment of the dean is critical, and needs to be clear, unwavering, and public (e.g., ASEE’s Engineering Deans Diversity Pledge). The challenge for a committed leader, however, is not identification of problems or evidence-based solutions, but rather matching appropriate approaches with organizational “readiness” [6]. A useful model for identifying an organization’s gender-diversity-awareness “starting place” is the Multicultural Organizational Development Model [7]. Launching change processes from a realistic understanding of the college’s current culture helps leaders ensure that evidence-based strategies applied to address identified problems, will meet with less resistance and achieve greater success.

In addition to identification of college “readiness” for change, conducting a college gender equity self-assessment is critical. What is the nature of the “playing field?” The EDGE initiative has developed a valuable 2-part EDGE College Gender Equity Self-Assessment Tool specifically designed for deans of engineering colleges, to assess gender equity issues, including issues of intersectionality of gender and race.

These three actions: dean commitment, assessment of college “readiness” for change, and collection of college-specific quantitative and qualitative gender diversity data, pave the way for identification of appropriate evidence-based strategies and resources. When identifying change strategies and resources, it is important to consider a systemic approach so that lasting change can be achieved.

Simmons University’s Center for Gender in Organizations developed a succinct, elegant, Framework for Promoting Gender Equity in Organizations which recognizes 4 Frames: Frame 1: “Equip the Woman” (i.e., help the individual cope within an inequitable system); Frame 2: “Create Opportunity” (e.g., create policies and procedures that help support gender equity), Frame 3: “Value Difference” (e.g., ensure that leaders value and actively promote diversity), and Frame 4: “Re-vision Work Culture” (i.e., recognize that correction is needed to underlying systemic organizational factors) [8]. Work in the last frame is instrumental for lasting organizational gender equity change.

Development of evidence-based programs, strategies, and tools that target the first three frames, are important stepping stones to the work of re-visioning the culture of the college. There are many examples of evidence-based tools (e.g., EDGE Checklist, Tools & Resources) that deans can use to help equip women for success, create equitable policies, and support gender-equity champions. However, achieving success in the first three frames does not mean that the hard work of sustaining gender diversity through re-visioning the college culture has been achieved. Frame 4 recognizes that gender is “not so much a biologic concept as a social construct,” and as such, gender equity change is ultimately not about women or discrimination, but the culture of the organization itself.

The EDGE Initiative seeks to provide strategies and exemplars of engineering deans leading the charge to “re-vision” the definition of excellence through gender diversity, equity and inclusion, and thus creating college competitive advantage.

Be sure to check the EDGE website for regular updates!

End Notes:

- William A. Wulf, Diversity in Engineering, 2008

- Scott Page, Diversity Bonus, 2017

3, McKinsey & Company, Delivery through Diversity, 2018

- 4. Abby Stewart & Virginia Valian, An Inclusive Academy: Achieving Diversity and Excellence, 2018

- Virginia Valian, Benefits of Ensuring Gender Equity, 2013

- Laurin Y. Mayeno, Stages of Multicultural Organizational Change, 2007 (pp. 21-30)

- Evangelina Holvino, Multi-Cultural Organization Development (MCOD) Model, 2008

- Simmons University Center for Gender in Organizations, Framework for Promoting Gender Equity in Organizations, 1998

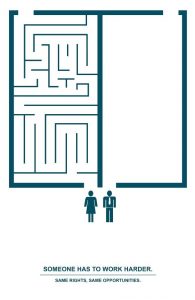

Image credit: Utilita Manifesta, Design for Social

https://www.behance.net/gallery/2598519/Manifesta-Utilita-human-rights